by Mark Murphy

Republished from Forbes, March 26, 2017

Imagine you’re a frontline employee and you receive word that you’re about to participate in a major change management initiative. You’ve performed your job a certain way for years, you’re quite good at doing it that way, and now your boss tells you that the processes that give you comfort and accomplishment are going to be upended. Whether it’s new technology or new processes or some new operational philosophy, you will no longer be able to do your job the same way.

Will you be as successful in the new environment as you were in the old one? Will you be as good at your job once the changes are made? It’s entirely possible that you will be every bit as successful, but it’s also possible that you won’t be. And that makes change management risky.

Some people love taking risks; the potential upside is far more compelling than any downside. Or they just love the adrenaline rush that comes from the gamble. But however many people love taking risks, there are much more that avoid risk (or take only very small risks). And that’s a message that is sometimes lost on senior executives.

More than 10,000 leaders and professionals have taken the free online test “How Do You Personally Feel About Change?” One of the questions asks respondents to select from these options:

• I like taking risks.

• I would take a risk if it seemed prudent.

• I avoid risks.

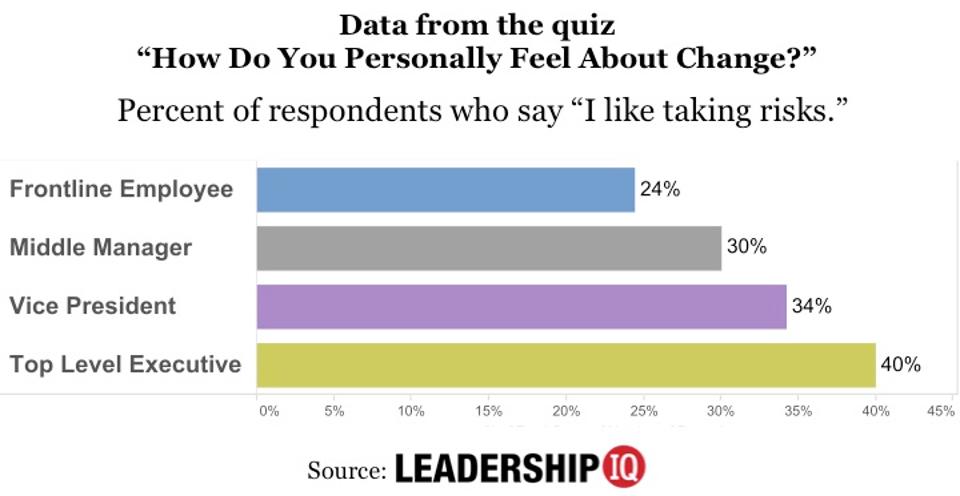

Overall, about 28% of respondents say that they like taking risks. If your company is going through a change management initiative that seems risky, you’re likely to run into some problems if only 28% of people like taking risks.

However, I discovered big differences in how people viewed change when I dissected the data by position. For instance, 40% of top executives like taking risks. But for frontline employees, that number is only 24%. So in the average company, the CEO is 66% more likely to enjoy taking risks than the employees.

The following chart shows the data for all job levels:

Credit: LeadershipIQ

There are several lessons here: First, if your change management initiative seems risky, especially in the eyes of employees, you’re probably going to have trouble generating lots of support. You might look at the riskiness and think ‘wow, this is really cool; finally some excitement!’ But given what the above data shows, it’s quite likely that your employees don’t view the riskiness quite so favorably.

Second, if you’re the executive who’s initiating this change management program, you probably have a very different assessment of what constitutes ‘risk’ than your employees. To you, this change might seem like the easiest thing ever. But are your employees going to see it that way?

To an Olympic long-jumper, leaping across a 10-foot wide stream filled with piranhas seems like nothing; they can leap 10-feet without breaking a sweat (the world long-jump record is over 29 feet). But I probably can’t leap 10 feet. Asking me to leap across a 10-foot wide stream filled with piranhas is pretty much the same as asking me to jump right into the middle of a stream filled with piranhas. For a world-class athlete, this jump doesn’t involve any risk at all; but for someone like me, it’s all risk with virtually no chance of success.

Third, senior executives like taking risks and they’re the ones who are initiating most change management efforts. But they’re not the ones who ultimately have to do the bulk of the work executing the change. And the people who will be doing that work (i.e. frontline employees) are not nearly as enamored of taking risks.

Now, I’m not saying that executives shouldn’t enjoy taking risks. Or that they shouldn’t initiate big change management efforts, even risky ones. But I am saying that executives need to be much more cognizant of the gap between their perspective and that of their employees. Because no matter how hard executives push for change, if their frontlines are paralyzed with risk-induced fear, the change effort is guaranteed to fail. And that reality should make every executive want to spend a lot more time and effort communicating about the change and taking steps to make it seem a lot less risky.

Finally, it’s worth asking ‘why do executives like taking risks more than their frontline employees?’ There are lots of possible reasons. Executives usually had to take some risks throughout their career to even make it to the executive ranks, so it’s likely that they see risk as positive. Also, executives are often well-compensated for taking risks that pay off, and they’re often not punished for taking risks that don’t. There are lots of executives who’ve gambled and lost big that are still employed. Frontline employees are much more likely to get fired for losing a risky bet than most executives.

You can’t eliminate all the riskiness from today’s corporate environment. Nor should you try. But if you’re asking employees to follow you on a risky change management initiative, you may want to pause and think about how you can make the journey seem a bit less risky.